Do Women Join the Military out of Patriotism?

October 15, 2012

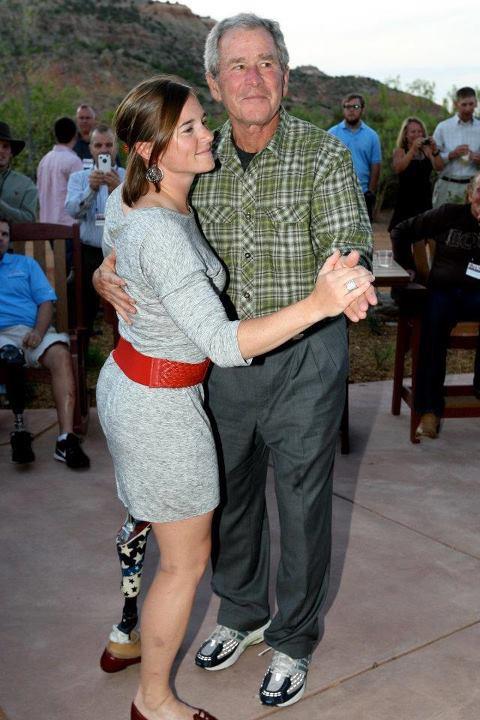

HERE is an undated photo from the Facebook page of the Tea Party showing George W. Bush dancing recently with an injured veteran. The sight of a woman dressed in military fatigues says a lot about what a society thinks of women. But the sight of a woman who has lost her leg in military action, having been deliberately put in harms’ way, says even more, painting a picture of a world that does not value, well, anything. It fills me with horror and disgust, not for this particular woman, who has been maimed permanently and deserves some compassion, but for the powerful institutions and leaders who have condoned this.

In the recent entry on women in the military, a female reader, an Air Force veteran who stated that she joined the military for solely economic reasons, says that women, purely on the basis of their patriotic sentiments, are an asset to the military as soldiers. Terry Morris, also a veteran, disagrees. He writes:

In short, while I agree with you that women CAN BE, and often are, patriotic Americans, I reject that patriotism, as defined above, is in general the chief motivating factor for female enlistments in the U.S. military today.

His comments are worth repeating in full:

Women can certainly be patriotic, Alyce, sure. No one is denying that, or even as much as implying that the opposite is the case, which would be … dumb.

But whenever one speaks of patriotism necessarily having a connection to military or some other form of government service, which is no more true than that non-military or other government service necessarily means non-patriotism or any lack thereof, I for one begin to question that person’s understanding of the term “patriotism.”

In other words, we do everyone a disservice when we equate military service (or other government service) to patriotism, since in doing so we’re essentially implying that one cannot be (fully) patriotic unless(s)he has served in the military/that military service automatically indicates patriotism. Neither of which is true.

Here is Webster’s 1828 definition of the term:

“Patriotism, n. Love of one’s country; the passion which aims to serve one’s country, either in defending it from invasion, or protecting its rights and maintaining its laws and institutions in vigor and purity.”

The last phrase in the definition – and “maintaining its laws and institutions in vigor and purity” – is key to a proper understanding of the term “patriotism.” As well as, incidentally, of distinguishing between traditionalism and the various manifestations of liberalism, left and “right.” Feminism is, by definition, unpatriotic and un-American, since it seeks to undo everything traditionally American.

During my enlistment, I served with many women, and at the time – late ’80s-early ’90s – better than half of the women I served with were very open about the fact that they had not joined the military out of any sense of loyalty to the United States, its Constitution or its institutions. Indeed, they often complained that America was/is a “racist, bigoted, hate-filled, male-dominated country” whose institutions, such as the military, merely represented these unholy characteristics. And they were out to do their parts in changing this.

I will say that the white women I worked with, as opposed to black women and other minority women, were much more patriotic minded as a general rule. But even most of them, and several of them in particular that I can recall who exhibited a near perfect and complete hatred for everything America had once represented, and that some of us were still clinging to, retained an element of the feminist ideology which had been firmly instilled in them during their most formative years. In short, while I agree with you that women CAN BE, and often are, patriotic Americans, I reject that patriotism, as defined above, is in general the chief motivating factor for female enlistments in the U.S. military today.

What makes us presume that women are so much different today is that the culture is so much different today, and feminism is so much more institutionalized and influential today. Indeed, the institutionalization of feminism in the U.S. military bears a direct connection to the introduction of open homosexuality in the military.

Plus, I’ve seen this first hand, so I know it to be fact, not just conjecture on my part.

The women you mention who’ve served in some of our wars “dressed as boys” constituted an anomaly that was certainly not encouraged. And that is the point when you boil it all down. If there is any greater abomination than the ideal of the “female soldier,” to answer the question posed to head this entry, it is the ideal of the “gay/lesbian/bi-sexual soldier.” And we may rest in the assurance that you do not get the one without eventually getting the other.

—– Comments ——

Buck writes:

A U.S. citizen who serves the government/military is not necessarily a patriot, and is certainly not, if not an American. What has self-defense, say, joining the military for the expressed purpose of defending the United States against attack, got to do with patriotism? The instinct to survive is not what motivated America’s first patriots to fight. They could have survived just fine under the rule of the King George. What does a military career or temporary job have to do with patriotism? Nothing.

Mr. Morris writes:

In defense of Mr. Webster, whom I have come to greatly admire, and not only for his original dictionary, the fault is not his, but mine, that the (partial) definition I included in the post failed to mention citizenship. What I included was from memory. Here is the rest of Webster’s definition (which admittedly I had to look up, since I could not quote it word for word):

“Patriotism is the characteristic of a good citizen, the noblest passion that animates a man in the character of a citizen.”

Concerning Buck’s comments about the founding generation, he seems to be saying that patriotism, to them, meant more than mere survival, since, as Buck rightly states, they could have “survived” just fine under the rulership of King George. And I wholeheartedly agree. It is a good point.