Crusoe Speaks

June 7, 2010

[This is the first installment in my series “A Tale of Eternal Thoughts.”]

Dear Reader,

You have a bright and inquiring mind. It is elegant, systematic and logical. That millions of others possess minds similar to yours does not diminish its magnificence. Trillions of stars fill the heavens; does this mean any one burns less brightly?

A machine is switched on and off. A star burns unconsciously. Your mind is exhilaratingly independent. It seems to burn with its own mysterious, self-replenishing fuel. Even so, you thrive on the world as it is. You test every supposed truth against hard, cold reality.

Knowing what I do about you, I would never attempt to tell you something untrue. Nor would I tell you something fanciful and imaginary simply because I wanted to entertain you. If I’m going to entertain you, I’m going to do so with the truth. You deserve nothing less.

For this reason, I must warn you that the account that follows has the appearance of improbability. There may be moments when you suspect you have been thrown into a hoax. Knowing you, there are two ways you test the truth of a proposition. First, you look for concrete verification. Second, you assess the authority of the person telling you the so-called fact. For instance, when you were told that Isaac Newton discovered the laws of gravity, you believed it even though you never saw Mr. Newton discovering the laws of gravity. You took it on the authority of someone, perhaps your grade school teacher or the author of a book.

I cannot offer you evidence that what I say is true. As for authority, I am a housewife. Housewives are either too guileless to lie or too transparent in their manipulations. The world, according to experts, has been ruined by bad mothers. Psychologists, as well as ordinary people, have seen through their games. That’s because mothers lack the skill to cover their traces.

Therefore you can take my word when I tell you in all sincerity that I have seen Robinson Crusoe with my own eyes.

The exact location of my whereabouts when I met Mr. Crusoe cannot be divulged at this time. I am offering an eyewitness account below. I ask you to gloss over a few confusing parts in the narrative. For instance, when I refer to “Socrates lying in state,” please do not ask me any questions just yet. I know this is an offense to your curiosity. You should never have to suspend your right to know. Nevertheless I ask you to be, for a very brief time, just a little less inquiring.

Sincerely yours,

Laura Wood

Daniel Defoe tapped the microphone three times. Testing, one two three. Testing, one two three. His voice was barely audible.

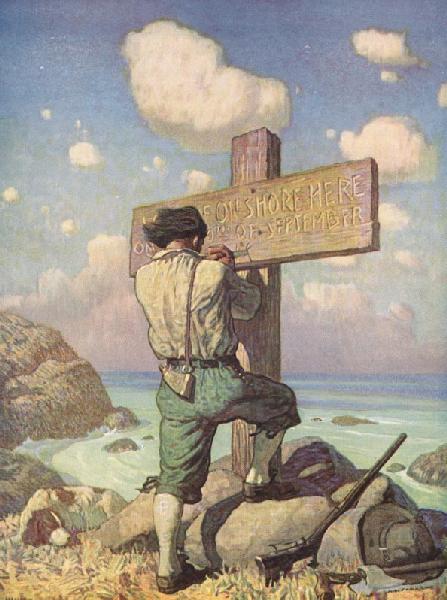

A man in ragged patched pants and a goatskin cap put down the rifle in his hand and came to the podium. He turned the microphone upside down and found a tiny knob on the bottom. He adjusted it and then returned the microphone to the podium.

Testing, one two three. Testing, one two three. Defoe’s voice sounded through the cavernous hall. A few rows of seats, about forty in all, were set up in front of the podium and a hand-written sign on an easel read, Tuesday Morning Coffee Hour.

I had just left the room where Socrates lay in state and climbed the stairs to the main hall. I passed a table piled with pastries. I took one, and then found a seat in the third row. Others straggled in and soon the seats were mostly filled. A woman in a long dress with visible petticoats, the sort of gown worn by a shopkeeper’s wife in colonial Virginia, plopped herself into the seat to the right of me and loudly exhaled. Her capacious bosom strained at the front laces of her gown like the pulp of a ripened fruit about to split its skins. She held a paper sack of peppermints and tossed one into her mouth.

An elderly gentlemen took a seat to her right. He wore a battered helmet and a dented breastplate. Before he sat down, he left a long lance standing against the wall. His face was furrowed and dusty.

The crowd settled in its seats and a hush fell on the gathering. Defoe – the famous British journalist, novelist, pamphleteer and bankrupt businessman – took to the microphone.

“Excellent to see you,” he said, thrusting his hands into his vest pockets. He held his nose in the air for a moment and composed himself. This slight motion was sufficient to slightly dislodge his curly grey wig.

“The topic of today’s Coffee Hour is Solitude,” he said, pausing for dramatic effect. “I am here to present to you history’s foremost authority on the subject. We mustn’t delude ourselves into thinking that we do not know him. For we all know him. We know him in our minds and in our hearts and in our souls. Wherever we are and whoever we are, we know him. In some essential ways, ladies and gentleman, he is us.”

The author and polemicist, who had once met scorn with pride and never looked back, held his nose high again, as if it had been tugged upward by an invisible string.

“He is, of course, the eminent Robinson Crusoe, friend and advocate of the world’s castaways.” He pointed to Crusoe, none other than the ragged man who had fixed the microphone. Crusoe stood and made an awkward bow.

DeFoe beamed. “As we all know, Mr. Crusoe led a life of unexampled misfortunes. Here is invincible patience under the worst of misery; indefatigable application and undaunted resolution under the greatest and most discouraging circumstances.”

“Most discouraging!” mumbled the woman with the peppermints.

“I have heard,” DeFoe continued, “that the envious and ill-disposed part of the world have raised some objections against the account which I composed of Mr. Crusoe’s misfortunes. They say the story is feigned, that the names are borrowed and that it is all a fiction, that there never were any such man or place, or such circumstances in any man’s life; that it is all formed and embellished by invention to impose upon the world.”

The woman to the right leaned her prodigious chest toward me, slurped a peppermint into a rear alley of her mouth and whispered, “I can tell you every word of it is true.”

“I hereby declare their objection is an invention scandalous in design, and false in fact. The story is historical,” said DeFoe, wagging his right hand vigorously and upsetting ever so slightly the hairpiece on his head.

“Now before our speaker takes to the podium, a few details of his history are in order.”

DeFoe pulled a large board from behind the podium and set it on an easel. It bore a map of the world with prominent arrows pointing away from the coast of England, swinging past Spain and down the coast of Africa and then veering westward to a tiny spot near South America.

The author held a pointer in his right hand. “Now as you can see our friend’s journey began here in York,” he said, tapping the pointer on northern England. “This was where Crusoe lived with his family, still a young man and bent on finding his fortune in the world. As you know, his father kindly offered him all the help a loving father can give to a son on the brink of adulthood, but Crusoe sadly declined it for a life at sea.” DeFoe furrowed his brows and glanced at Crusoe.

“Such was the headstrong foolishness of Crusoe and his determination to become a sailor despite his father’s admonitions, that he headed for a ship from London bound for Africa.”

“His first trip as a man of the sea was a success, but the second only confirmed his father’s wisdom. Crusoe was taken hostage by Muslim pirates and made a slave right about here,” he said, tapping North Africa.

“With the help of a slave boy, he managed to escape and was picked up by a Portuguese trading vessel, which provided him with passage to Brazil. All seemed well for a time. Crusoe became a modestly successful plantation owner. But he could not avoid evil temptations to make a larger income and outfitted a ship bound for Africa for slaves.”

“Our hero was vulnerable to the most unwholesome of influences and I encourage all and sundry to look on this expedition as a sin of his distant past.”

“Now here we come to the heart of his story. Right about here,” he said, pointing to spot about 10 degrees latitude above the equator and just east of Trinidad, “Crusoe’s ship encountered a fierce storm. Make no mistake about it. It was a gale of superhuman dimensions. All of the men but Crusoe were lost on the ship and he swam to shore.”

DeFoe walked in front of the podium and stopped. His nose received its tugging and the wig slipped closer to his left ear.

“Enormous curiosity has been expended on Crusoe’s survival on this destitute island for 28 years. How did he feed himself? How did he find shelter?”

“I think you’ll all agree that Crusoe is a most resourceful man. He answers these questions in detail in the journal he kept of his island existence. More importantly, he answers the natural curiosity about his psychological survival. All of us want to know how a man successfully weathers the storms of extreme solitude. The whole world, you might say, hangs on the example of Crusoe. If he can manage on a deserted island for almost three decades, well, then we can manage the natural solitude we might feel in the very midst of a bustling city on a busy day.”

A man with a wooly gray beard raised his hand from the back row. “Did he keep a record of the animal species on the island?”

“No, I’m afraid he did not catalogue every species. Crusoe was a practical man, pre-scientific, you might say. However, feel free to speak to him later to glean what you can from his observations.”

Another man in the back waved his arm. “Is Crusoe’s island anywhere near Lilliput?”

“Good God, man, do you know anything about geography? The island of Lilliput is southwest of Sumatra and the Sunda Straits. Crusoe was here east of Trinidad and the Orinoco River in Venezuela. Entirely different part of the world.”

Yet another member of the audience called out, “Did he ever try any kind of hot sauce on his goats?”

“Now everyone please, please,” said DeFoe, putting down his pointer. “Perhaps Crusoe can go into some of this, but remember his theme. His theme! This is not a seminar in natural history or geography or culinary arts, as worthy as these subjects are, but on the psychological consequences of extreme solitude. You have all of eternity to explore these other matters, let’s adhere to our topic.”

“What is your name?” the woman with the peppermints whispered to me.

“You can just call me Mrs. W.,” I said.

“Pleased to meet you. And, I’m Moll Flanders. Would you care for one?”

I took a peppermint.

“There are so few women here,” Moll whispered.

“Sh-sh-sh-sh!” Defoe said sharply.

“Without further ado, please welcome today’s guest speaker, ladies and gentlemen,” he said. “Mr. Robinson Crusoe.”

Crusoe rose and shyly bowed. He hesitantly walked to the podium to applause and stood with his hands at his sides and his eyes cast down.

“I, uh, yes, I, uh, that, you see, was the island where I spent so many years. At first I cursed my fate, uh, yes, but, you see ….” His words trailed off. The castaway seemed to be in pain of some kind. He shuffled his feet, coughed and wiped sweat from his upper lip. They waited for him to recover his nerve, but there was a long awkward pause.

Crusoe took a gulp of air and began again. “There were moments, you see, as I walked about, either on my hunting, or for viewing the country, you see … ” He filled his starved lungs once more.

“The anguish of my soul at my condition, yes, um, it would break out upon me on a sudden, and my very heart would die within me.”

“What a shame!” Moll whispered to me, her new friend.

He took another gulp. “To think of the woods, the mountains, the deserts I was in; yes, you see, and how I was a prisoner, locked up with the eternal bars and bolts of the ocean in an unfinished wilderness, without redemption….”

Another gulp. “In the midst of the greatest composures of my mind, yes, you see, this would break out upon me like a storm, and make me wring my hands, and weep like a child.”

“Sometimes, it would take me in the middle of my work, and I would immediately sit down and sigh, and look upon the ground for an hour or two together; and this was still worse to me; for if I could burst out into tears, or vent myself by words, it would go off, and the grief having exhausted itself would abate.”

“One morning being very sad, um, you see, I opened the Bible retrieved from the ship upon the words, I will never, never leave thee, nor forsake thee; immediately it occurred, that these words were to me. Why else should they be directed in such a manner, just at the moment when I was mourning over my condition.”

“He is adorable,” whispered Moll, who had moved her chair closer to me. “I never did find a simple God-fearing man for any of my five husbands.”

“Sh-sh-sh!” snapped Defoe.

“Well, then, said I,” continued Crusoe, “if God does not forsake me, of what ill consequence can it be, or what matters it, though the world should all forsake me, seeing on the other hand, if I had all the world, and should lose the favor and blessing of God, there would be no comparison in the loss?”

“He is positively theological,” Moll said, barely mouthing the words and gesturing to me to take another mint.

Crusoe took a very large gulp. “From this moment, I began to conclude in my mind, that it was possible for me to be more happy in this forsaken solitary condition, than it was probable I should ever have been in any other particular state in the world.”

“I was removed from all the wickedness of the world. I had nothing to covet. I was Lord of the whole manor, or if I pleased, I might call myself King, or Emperor of the whole country over which I had possession of. There were no rivals. I had no competitor, none to dispute sovereignty or command with me. I had corn enough. I had tortoises and turtles enough. I had timber enough to have built a fleet of ships. I had grapes enough to have made wine, or to have cured raisins, to have loaded that Fleet, when they had been built.”

“These reflections made me very sensible of the goodness of Providence to me, and very thankful for my present condition with all its hardships and misfortunes.”

“How sweet!” whispered Moll, “I never once was thankful for my hard ships. Never once.”

No longer able to contain her intellectual yearnings, Moll raised her hand.

“Did you ever experience any…. cravings of the flesh while you were on your island, Mr. Crusoe?” she asked, embellishing her words with an expression of such demure innocence one would have thought no man had ever laid his weary head on her prodigious cushions.

“Well, yes, at first, I – “

Defoe, who was seated in the front row, stood up. “As for your appointed theme of Solitude, Mr. Crusoe, we would be interested in learning something about how you handled the demands of society once you returned to civilization.”

“Yes, um,” said Crusoe. “Certainly, um, yes.”

“You see, it was a great while after I came into human society that I felt some regret at the loss of the solitary hours and retirements I had in the island. Yes, I felt sorely the loss of my contemplations.”

“But, then, you see, I came to realize that I could retain the best of my island existence in the very midst of throng. Let no man plead that he wants retirement, that he loves solitude, but cannot enjoy it. ‘Tis all a delusion; if he loves it, if he desires it, he may have it whenever, wherever and as often as he pleases.”

“How dreadful,” whispered Moll.

“Let the man who would require the advantages of solitude, and who understands the meaning of the word, learn to retire into himself.”

“A most unwise suggestion.” Moll was growing peeved. A look of outright suspicion fell onto the tattered shipwreck.

“Let such never afflict themselves that they cannot retreat from the world. Let them learn to retreat in the world, and they shall enjoy a perfect solitude as complete, to all intents and purposes, as if they were to live in the cupola of St. Paul’s, or as if they were to live on the top of Cheriot Hill in Northumberland.”

“Who would want to live in a cupola, I ask you, my dear?”

“There is no need of a wilderness to wander among wild beasts, no necessity of a cell on the top of a mountain, or a desolate island in the sea; if the mind be confined, if the soul be truly master of itself, all is safe.”

Crusoe had lost all reserve. Indeed, he was so given over to his oratory and had so stirred the imaginations of those present that each and every member of the audience privately envisioned himself on a desolate island in the middle of the sea or in a private oasis amidst a teeming city. Solitude seemed the most exalted of conditions.

There was a warm round of applause. As Crusoe spoke this paean to isolation, a new guest arrived. He was about five feet six inches tall, slightly hunched at the shoulders, strongly built, with a jutting brow and hair covering most of his body. He was stark naked, his ample manhood on display for this most civilized of audiences. No one seemed to take much notice, but Moll was visibly pleased. She batted her eyes. The guest took a seat and, at that moment, Defoe stepped to the microphone.

“Nicely done, my friend,” he said to Crusoe. “No one else can discourse on this troubling subject with more profound delicacy and understanding.”

“Now, as much as we are all interested in Crusoe’s psychological observations, I know many of you are equally fascinated by the knowledge he acquired on his island in the arts of simple survival. Indeed, survival, in its most elemental form, with all the forces of nature arrayed against the daily continuance of human existence, is a subject that holds particular interest now that it is so remote from us, does it not?”

Many sat up in their seats. They exchanged barely visible nods of agreement.

“Indeed, some of you have challenged the account of his adventures, contesting the ability of a solitary human being to build adequate shelter, grow food and raise livestock in the wild.”

“Nonsense,” I say, “And to prove all this to you, I have a most delightful surprise.”

DeFoe drew back a curtain behind the podium. There before their eyes was a beach, replete with driftwood, a few wild goats, a cave, a homemade shack and a hammock. A small stand of cultivated barley and the fronds of a towering palm swayed in the breeze from an invisible sea.

A low din of conversation arose from the audience. Crusoe stepped onto the beach, picked up a tattered pair of shoes and moved them to the entrance of the cave, much as a proud homeowner might quickly remove the clutter of newspapers and slippers from his living room.

“Good man, good man,” said DeFoe.

“I’d like to invite all of you to step onto Mr. Crusoe’s island and see for yourself as he demonstrates his practical genius for survival. Incidentally, a foremost authority on the art of survival is among us today and he can most assuredly confirm whether Mr. Crusoe’s skills are genuine.”

“Mr. N., welcome. Will you please stand so all can know who you are?”

“Mr. N?” Defoe pointed to a back row. From his seat, the clothes-free man stood and bowed awkwardly.

“I hope you will all understand,” said Mr. DeFoe, “Mr. N. is still without all but rudimentary skills in language, a fact which does nothing to diminish his practical genius. As you probably already know, Mr. N. was the inventor of fire.”

Thunderous applause broke loose from the audience, which had tripled since the start of the lecture. Even the world-famous geneticist and a man hailed as the father of modern-day chemistry joined in, recognizing that their own genius was dwarfed by that of the silent Mr. N., who lived in the earliest dawn of human history.

For most of this interlude, Moll had sat in uncharacteristic silence, her gaze fixed on one object in the room: Mr. N. But, now, she rose suddenly and whistled and whooped. Falling back into her seat, she turned to me. “Fire!” she said in her loud whisper. “I am ablaze.”

She fanned her reddened bosom with a lace-edged handkerchief.

People began to crowd onto the beach. Crusoe and Mr. N. joined them and they were both surrounded by a circle of onlookers. Crusoe began to demonstrate the butchering of a goat through pantomime.

Mr. N. held two sharpened stones and knelt to the sand, preparing a small pile of debris. I could not see clearly, so thick was the crowd, but I heard sharp debates among the onlookers as to what precise tactics he would use. As Mr. N. began to rub the stones together there was utter silence. Only a moment or two passed before the slightest wisp of smoke rose from the debris and the primitive man lowered his head to tenderly exhale.

Ecstatic applause erupted as a modest flame shot up from the ground. Then there was sheer chaos as everyone began to talk and question all at once. Within minutes, the fire was roaring. So great was the intellectual ferment, I felt exhausted.

I headed down Crusoe’s beach toward the cave.